- 26/11/2025

- Blog

The Energy Challenge Facing British Aluminium

In this blog, we examine one of the most pressing challenges for primary aluminium production in the UK: energy.

Producing primary aluminium has always depended on a reliable, continuous supply of energy, as the smelting process demands an uninterrupted flow of electricity to sustain electrolytic reduction. In regions where energy frameworks recognise this industrial reality, smelters operate with the confidence that long-term cost stability affords. In the United Kingdom, however, the present market structure exposes energy-intensive producers to volatile conditions that undermine operational continuity, making the future of primary aluminium challenging. At Alvance British Aluminium in Lochaber, this challenge is experienced not as an abstract concept, but as a governing constraint that shapes how much metal can be produced, when it can be made, and whether Britain will retain this strategic capability at all.

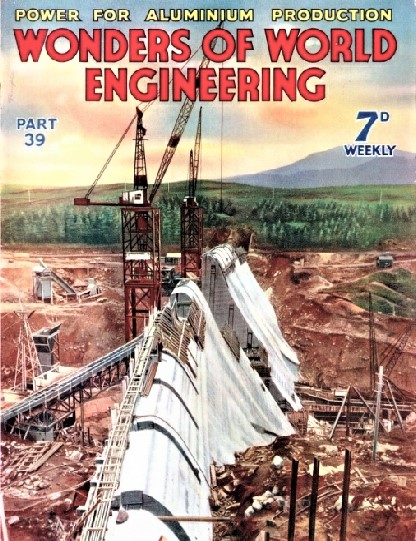

Thanks to the ingenuity of our forefathers, whose forward-thinking energy solutions continue to power Lochaber today.

For almost a century, the Lochaber smelter has been integrated with a dedicated hydroelectric scheme, designed to secure the baseload power required for aluminium production. This unique bond between renewable generation and heavy industry has enabled the operation to achieve one of the lowest carbon footprints in the global sector. Lochaber Smelter produces aluminium with a carbon footprint of 4.26 tonnes of CO₂ per tonne of metal, which is 70 per cent below the global average, drawing strength from our rural estate setting through JAHAMA Highland Estates, our hydro generation and the full chain of smelting and casting skills held on site. This long-standing alignment between low-carbon energy and strategic manufacturing should, in principle, offer the United Kingdom both a competitive and environmental advantage. However, broader national energy conditions have hardened to such an extent that even this advantage is now overshadowed by escalating exposure to market pricing.

Our hydroelectric station generates in the region of 500GWHs of renewable electricity each year. When operating at full smelting capacity, the site requires approximately 700GWHs. Historically, it was possible to bridge that shortfall by purchasing supplementary electricity at prices that aligned with aluminium production models; however, those conditions have changed. Over the past decade, UK industrial power prices have diverged sharply from those available to comparable producers in continental Europe, North America and Asia. Analysis by Ofgem and government documents confirms that British heavy industry is confronted with some of the highest wholesale electricity and network charges of any advanced economy. The impact of this disparity is not marginal; it permeates every tonne of metal produced using market-priced energy and eroding competitiveness.

Aluminium is traded on global exchanges, and its value is determined by international markets that do not recognise regional differences in power cost. A smelter in the Scottish Highlands sells metal at the same reference price as a producer in Europe, North America, the Middle East or Asia, yet many competitors operate in regions where long-term, generation-linked power arrangements are more common, helping protect energy-intensive industries from sudden swings in electricity prices. In hydro-rich countries such as Iceland and Norway, the structure of their energy systems can offer greater stability and predictability for continuous industrial loads. By contrast, the UK model remains rooted in short-term wholesale exposure, which was designed for flexible commercial demand rather than round-the-clock industrial processes like aluminium smelting.

Our own hydropower offers insulation, but not immunity, as the hydrological cycle must be managed with care, balancing reservoir levels across seasonal variations. Electricity output is influenced by rainfall, and generation capacity fluctuates accordingly. In recent years, production planning at Lochaber has been fundamentally reshaped to align with hydropower availability, avoiding reliance on Grid electricity where market conditions render such exposure unsustainable. This has required curtailment during periods when hydropower alone cannot meet demand. Curtailment affects employment, output, supplier networks, and regional confidence, yet it remains the only viable option when energy market prices surpass tolerable thresholds. Data from the National Grid and Ofgem have shown repeated seasonal spikes in industrial electricity costs, reinforcing a structural vulnerability that cannot be mitigated through operational efficiency alone. Read more here.

The nature of aluminium smelting makes this challenge particularly acute. A potline cannot be paused; continuous current is required to maintain liquid metal within the cells. Unplanned interruptions risk freezing the pots, damaging infrastructure, imperilling safety, and incurring recovery costs that could be irrecoverable to the best of businesses, exceeding any short-term energy saving. Restarting a fully curtailed smelter requires extensive intervention and significant capital expenditure, with no guarantee of technical continuity. These realities are widely recognised in nations with established aluminium industries, where long-term energy agreements are designed to ensure continuity rather than merely cost control. In a nutshell, these risks pose significant risks to an aluminium smelter.

There is a broader national dimension that extends beyond operational economics. Aluminium is a critical material in modern manufacturing. It underpins aerospace, defence, transport, construction, packaging, and increasingly the energy transition through its role in wind turbine components, electric vehicle platforms, and high-voltage electricity transmission. Assessments by the International Energy Agency have identified aluminium as one of the essential raw materials for achieving global net-zero commitments. See more here.

Yet the United Kingdom risks becoming entirely dependent on imported primary metal, much of which is produced using power sources with far higher emissions.

The European Commission studies have already warned of strategic vulnerability when domestic capability is surrendered in favour of overseas supply. The consequences of such surrender are not easily reversed. See more here.

It is often suggested that downstream rolling and recycling capabilities may suffice in place of domestic smelting. While these remain vital, they cannot replace the security offered by sovereign primary production. Secondary aluminium relies on primary feedstock to maintain volume, and imported metal introduces uncertainty of origin, carbon intensity, and supply stability. If primary production in the UK were to cease, it would not simply be a reduction in capacity; it would be the loss of a strategic asset, a skilled workforce, and nearly a century of industrial roots tied to locally generated power.

The presence of the hydro scheme at Lochaber demonstrates what can be achieved when renewable infrastructure is integrated with strategic industry. Yet the existence of clean power is not sufficient when national energy frameworks treat constant baseload demand as interchangeable with flexible commercial consumption. This raises a fundamental question about industrial direction: if even a hydro-powered smelter cannot withstand UK market exposure, what future is there for energy-intensive industries that rely on energy market pricing?

There remains an opportunity to realign; a future energy strategy that supports foundational industry would not require subsidisation, but rather structural clarity. Long-duration power frameworks, greater recognition of baseload requirements, and most importantly, mechanisms that reflect generation cost rather than speculative market pricing would restore competitiveness without distorting markets. Many of Britain’s industrial peers have already adopted such approaches not as protectionism, but as strategic foresight.

At Alvance British Aluminium, the commitment to Lochaber is enduring. The workforce, apprentices, and supply chains that surround the smelter are embedded within the Highlands. We believe that aluminium should remain part of Britain’s industrial future, not a relic of its past. To do so, energy policy must evolve to recognise the importance of retaining the capability to produce critical materials domestically. Without such recognition, the United Kingdom risks consigning itself to dependency at the very moment its ambitions for energy transition and industrial sovereignty demand the opposite.

The choice is not simply between energy cost models; it is between retaining capacity or accepting permanent loss. With the right framework, the Highlands can continue to demonstrate how clean energy and heavy industry can operate in partnership. Without it, that partnership cannot be sustained. The decision will shape whether Britain remains a producer of strategic material or merely a consumer of it.

We work closely with the UK and Scottish Governments, as well as through our involvement in Make UK and European Aluminium, to ensure that the voice of hydro-powered aluminium production in Lochaber is represented in national and international policy discussions.

Latest News

View All Press Release

Press Release

JAHAMA Highland Estates announces major Scottish Highlands native woodland recovery plan

Multi-enterprise rural business JAHAMA Highland Estates has today announced one of the UK’s largest woodland regeneration schemes, committing to quadruple...

Read More Blog

Blog

How primary aluminium is made in Lochaber

Aluminium is used in almost every part of daily life, from vehicles and buildings to packaging and technology. It is...

Read More Press Release

Press Release

Unsung hero of Glasgow climbing scene, Willie Gorman, honoured in top mountain award

The Fort William Mountain Festival has this week awarded its 19th annual Scottish Award for Excellence in Mountain Culture, sponsored...

Read More News

News

Restoring Landscapes to Support Sustainable Aluminium Production

Recently, we welcomed the British Dragonfly Society (BDS) to our Mamore Estate on Jahama Highland Estates as part of our wider...

Read More Press Release

Press Release

Alvance British Aluminium recognised nationally for developing future talent

Alvance British Aluminium has been recognised at the Make UK Manufacturing Awards, reaching the national finals in the Developing...

Read More News

News

Your Future Career in Lochaber 2026 – Limited Spaces Available

We’re delighted to welcome you to Your Future Career in Lochaber, taking place on Wednesday 4 March 2026, 3pm–6pm, at...

Read More Blog

Blog

Why Skills, Housing and Transport Are Essential for Highland Industry

Alvance British Aluminium operates one of the most unique industrial sites in the UK. Our Fort William smelter produces aluminium...

Read More Press Release

Press Release

Christmas Celebrations Bring Colleagues & Families Together in Lochaber

Alvance British Aluminium and Jahama Highland Estates recently held their annual Christmas party for employees and their families, continuing a...

Read More